Jan 31 2015

Researchers at the University of Miami (UM) Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science developed and tested a new sensor to detect ambient levels of mercury in the atmosphere. Funded through a National Science Foundation Major Research Instrumentation grant, the new highly sensitive, laser-based instrument provides scientists with a method to more accurately measure global human exposure to mercury.

The measurement approach is called sequential two-photon laser induced fluorescence (2P-LIF) and uses two different laser beams to excite mercury atoms and monitor blue shifted atomic fluorescence. UM Rosenstiel School Professor of Atmospheric Sciences Anthony Hynes and colleagues tested the new mobile instrument, alongside the standard instrumentation that is currently used to monitor atmospheric mercury concentrations, during the three-week Reno Atmospheric Mercury Intercomparison Experiment (RAMIX) performed in 2011 in Reno, Nevada.

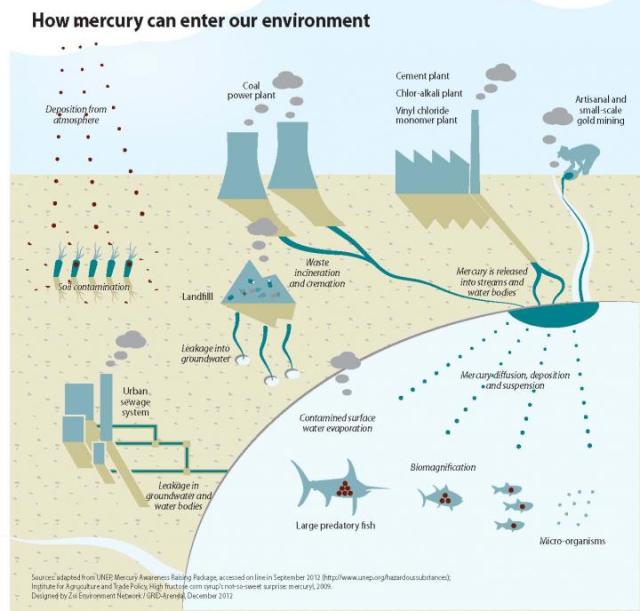

This graphic shows how mercury can enter the environment. Credit:UNEP Chemicals Branch, DTIE - Switzerland

This graphic shows how mercury can enter the environment. Credit:UNEP Chemicals Branch, DTIE - Switzerland

The 2P-LIF instrument measured ambient mercury at very minute levels within 10 seconds, whereas its counterpart instrument requires at least 2.5 minutes and is not able to differentiate between elemental and oxidized mercury, where the mercury atom is combined with another element or elements and becomes more efficiently deposited in the environment.

"To understand how mercury gets deposited we need to understand its atmospheric chemistry, but our understanding is very limited," said Hynes, a co-author of the new study. "Our instrument has the potential to greatly enhance our understanding of the atmospheric cycling of mercury and increase understanding of the global impact of mercury on human health."

The U.S. EPA Mercury and Air Toxics Standards and the International Minamata Convention on Mercury, have focused on limiting the emissions of toxic air pollutants, including mercury. Hynes noted that these represent huge steps forward but their effectiveness in protecting human health may be limited without an increased understanding of the global cycling of atmospheric mercury.

Mercury is deposited on the ground (dry deposition) or via rainfall (wet deposition) where it bioaccumulates and biomagnifies, ending up at much high concentrations in fish and mammals. Direct exposure to mercury by humans is primarily through the ingestion of methyl mercury from fish consumption.