Nov 24 2015

How thin can a camera be? Very, say Rice University researchers who have developed patented prototypes of their technological breakthrough.

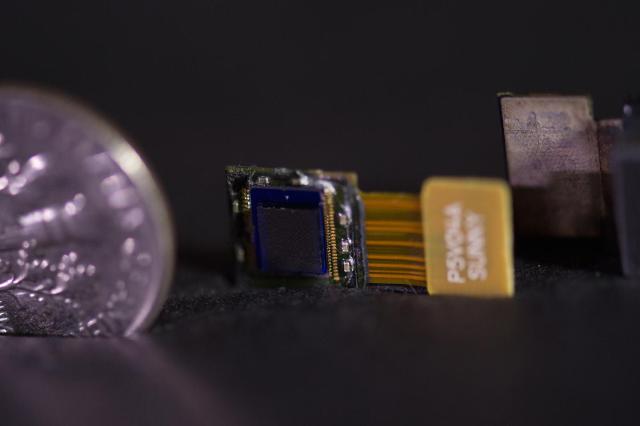

Rice University's FlatCam, thinner than a dime, is a new technology that shows promise to turn flat, curved or flexible surfaces into cameras. The device is based on a standard imaging sensor paired with a mask and decoding software. Credit: Jeff Fitlow/Rice University

Rice University's FlatCam, thinner than a dime, is a new technology that shows promise to turn flat, curved or flexible surfaces into cameras. The device is based on a standard imaging sensor paired with a mask and decoding software. Credit: Jeff Fitlow/Rice University

FlatCam, invented by the Rice labs of electrical and computer engineers Richard Baraniuk and Ashok Veeraraghavan, is little more than a thin sensor chip with a mask that replaces lenses in a traditional camera.

Making it practical are the sophisticated computer algorithms that process what the sensor detects and converts the sensor measurements into images and videos.

The research team will deliver a talk about its work at the Extreme Imaging Workshop Dec. 17 in Santiago, Chile, and have published a paper available via the online service ArXiv.

Traditional cameras are shrinking, driven by their widespread adoption in smartphones. But they all require lenses - and the post-fabrication assembly required to integrate lenses into cameras raises their cost, according to the researchers.

FlatCam does away with those issues in a camera that is also thin and flexible enough for applications that traditional devices cannot serve. FlatCams can be fabricated like microchips, with the precision, speed and the associated reduction in costs, Veeraraghavan said. Without lenses, he said, the most recent prototype is thinner than a dime.

"As traditional cameras get smaller, their sensors also get smaller, and this means they collect very little light," he said. "The low-light performance of a camera is tied to the surface area of the sensor. Unfortunately, since all camera designs are basically cubes, surface area is tied to thickness.

"Our design decouples the two parameters, providing the ability to utilize the enhanced light-collection abilities of large sensors with a really thin device," he said.

FlatCams may find use in security or disaster-relief applications and as flexible, foldable wearable and even disposable cameras, he said.

The researchers are realistic about the needs of photographers, who are far more likely to stick with their lens-based systems. But for some applications, FlatCam may be the only way to go, Baraniuk said.

"Moving from a cube design to just a surface without sacrificing performance opens up so many possibilities," he said. "We can make curved cameras, or wallpaper that's actually a camera. You can have a camera on your credit card or a camera in an ultrathin tablet computer."

FlatCam shares its heritage with lens-less pinhole cameras, but instead of a single hole, it features a grid-like coded mask positioned very close to the sensor. Each aperture allows a slightly different set of light data to reach the sensor. Raw data sent to the back-end processor - for now, a desktop computer - is sorted into an image. Like much larger light field cameras, the picture can be focused to different depths after the data is collected.

Rice's hand-built prototypes use off-the-shelf sensors and produce 512-by-512 images in seconds, but the researchers expect that resolution will improve as more advanced manufacturing techniques and reconstruction algorithms are developed. The FlatCam team is working with the Rice lab of Jacob Robinson, an assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering, to develop next-generation, directly fabricated devices.

The prototypes do not have viewfinders. Many applications won't need one, said co-author Aswin Sankaranarayanan, but a cellphone screen may eventually serve the purpose. "Smart phones already feature pretty powerful computers, so we can easily imagine computing at least a low-resolution preview in real time," he said.