Dec 17 2015

A typical environmental monitoring satellite is a big deal, literally. These satellites contain thousands of kilograms of remote sensing equipment, hurtling through space, making critical observations.

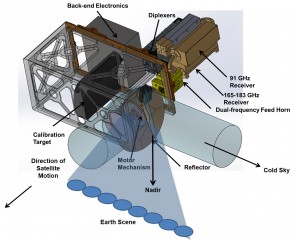

A schematic illustration of the TEMPEST-D instrument. Credit: Sharmila Padmanabhan

A schematic illustration of the TEMPEST-D instrument. Credit: Sharmila Padmanabhan

Colorado State University researchers are creating the next generation of such monitoring satellites. They are doing it at a hundredth the size and weight scale, though, by using not just one, but a constellation of satellites.

Supported by an $8.2 million NASA award managed by the Earth Science Technology Office, a team led by Steven Reising, professor of electrical and computer engineering, is developing instrumentation for satellites about the size of a hardback dictionary, called CubeSats, that can observe, in real time, a storm as it grows and progresses. They will demonstrate their technology aboard a launch awarded by NASA earlier this year.

Their project is called the Temporal Experiment of Storms and Tropical Systems – Demonstrator, or TEMPEST-D.

TEMPEST-D will demonstrate the ability to monitor the atmosphere with small satellites. The team will demonstrate a radiometer aboard a 6U CubeSat (30 cm by 20 cm by 10 cm, or about 12 inches by 8 inches by 4 inches), and subsequently plan to deploy a constellation of satellites to study cloud processes.

V. “Chandra” Chandrasekar, professor of electrical and computer engineering, a co-investigator on the program, also works on the Global Precipitation Mission (GPM), an international network of satellites providing the state of the art in rainfall and snow monitoring.

Reising, Chandra, and co-investigator Christian Kummerow, professor of atmospheric science and director of CSU’s Cooperative Institute for Research on the Atmosphere (CIRA), are working to demonstrate the utility of a single CubeSat now, then a constellation of them later, to conduct systematic and routine measurements over the globe.

Their long-term plan is to deploy a constellation of CubeSats that can perform rapid overpasses of developing storms, taking thousands of images inside clouds. The TEMPEST-D team includes key partners at NASA/Caltech’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, Calif. The JPL effort is led by Project Manager Todd Gaier.

“We are trying to improve our understanding of the processes in storms leading to rain, snow and other precipitation,” Chandra said.

The biggest technical challenge? Squeezing many of the capabilities of a large satellite into one that weighs just 8 kilograms (17.6 lbs.). Reising’s team has spent over a decade working to miniaturize a microwave radiometer to fit inside a CubeSat.

“We will be able to observe storms in ways not yet possible with the current fleet of satellites in orbit,” Reising said.