Mar 17 2017

(Credit: University of Rochester)

(Credit: University of Rochester)

When her medications are not giving her the relief, Bernadette Mroz says, “my world goes into a spin cycle. I cannot function mentally, emotionally, or physically.”

Mroz suffers from Parkinson’s disease, and does not expect a cure in her lifetime. However, she hopes that researchers at the University of Rochester will soon be able to fine tune the medications to control her memory lapses and tremors.

Toward that end, Mroz a resident of Hannibal, New York, recently took part in a Rochester clinical trial where she wore five sensors - one on her chest and the other four on her limbs. Thirty times a second, acceleration in three directions were recorded by each sensor - effectively recording Mroz’s every movement, including tremors, for a total of 46 hours.

The sensors provide an increasing amount of data on the progression of her disease. This data would be helpful for physicians to make better informed decisions about treatments being given to her, including adjustments made to her medications.

Instead of treating all patients as averages, which none of us are, we will be able to customize treatment based on individual data.

Gaurav Sharma, Professor, University of Rochester

He and the University neurologist Ray Dorsey are conducting a study, which they hope will help enhance treatment of patients suffering from Huntington’s or Parkinson’s disease.

Dorsey and Sharma are employing BioStampRC sensors, produced by MC10, a biomedical health care analytics company. Scott Pomerantz, the company’s CEO who received a bachelor’s degree as well as an MBA from Rochester, is also supporting the study.

The Challenge

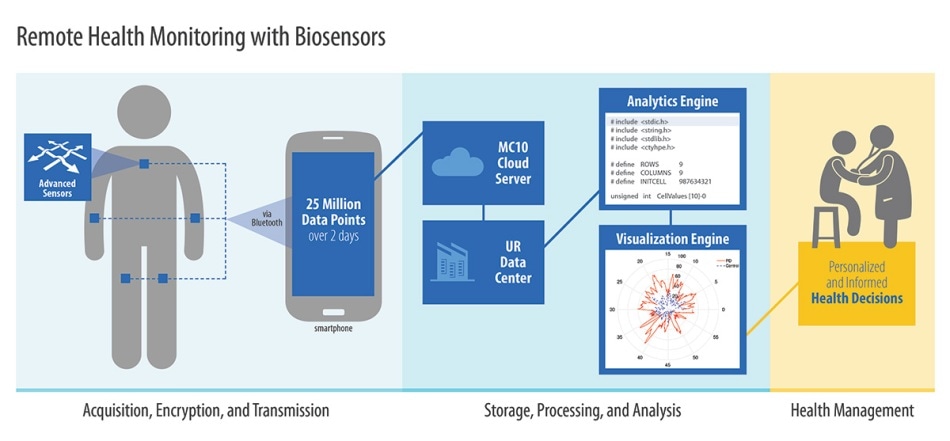

It was a challenge to analyze 25 million measurements produced by these sensors for each patient spanning 48 hours, and to present the results such that they are intelligible to a physician.

Thanks to data science, and especially machine learning, computers have the ability to learn with no explicit programming.

Sharma and Karthik Dinesh, a graduate student in his lab, employ processing algorithms in order to correlate the signals collected from the five sensors. The signals are converted into signal features to help measure tremor intensity and coordination.

Machine learning methodologies, such as classification and clustering, help to categorize how the two attributes can vary among patients who may be at various phases of the disease, and from individuals without the disease, who serve as controls. Efficacy of the medication can also be assessed, as machine learning helps categorize whether participants have taken their medication.

“We’ve just scratched the surface in terms of the depth of data we have to work with,” Sharma says.

The second part of the challenge is to translate all these for the caregiver.

If you tell a physician you have to look at two gigabytes of data to figure out what’s going on with your patient, you don’t have a chance. But if you can present the data in easily digestible plots and visualizations, the physician can comprehend it and act on it. This is a two-way conversation. It’s not like I can sit in my office and come up with the best way to do this. I have to ask the physician ‘what are the attributes that would be most relevant to you and what would be the presentation of data that would make the most sense?

Gaurav Sharma, Professor, University of Rochester

A Better Scenario

Currently, patients suffering from the unsteady gait and jerky movements of Huntington disease, or the tremors of Parkinson disease perform several motor activities when they visit their doctor. A movement disorder specialist uses a scaling system of 0 to 4 to rate the symptoms of the patients.

Such observations are subjective by nature and episodic, although they provide information and have been the standard for diagnosis and evaluation of movement disorders.

A very different scenario can result from the new research. Two days prior to their appointment, patients can purchase a pack of five adhesive patches with embedded electronic sensors from their neighborhood pharmacy, and place them on their skin. This allows them to obtain far more comprehensive and accurate measurements than are possible by a visit to a doctor’s office.

Currently, the individuals participating in the research mail their patches back to the researchers. However, Sharma and Dorsey say, the next-generation sensors being developed by MC10, can wirelessly transmit the data to a patient’s smartphone, and from there on to a secure database for analysis.

Patients residing in the most remote areas could be monitored from their homes. The new patches are also unobtrusive that they appear to be temporary tattoos.

In 2005, when Dorsey arrived as a fellow at the University, smartphones had just been introduced in the market. Today, they enable “anyone, anywhere to participate in research; anyone, anywhere to receive care,” he says. According to Dorsey, the combination of skin sensors, smartphones, and machine learning will allow researchers to perform clinical trials “in shorter periods of time, with smaller numbers of participants, giving us more objective assessments about whether drugs or devices are beneficial.”

“This will transform the way we care for patients with Parkinson and Huntington disease.”

In 2004 Mroz was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. Then by 2010, she had to stop working, and subsequently discontinue her driving too. However, she does not want to adopt what she calls the “woe is me” attitude seen in some Parkinson’s patients. She enthusiastically takes part in clinical trials conducted at the University, and volunteers as a board member at a local humane society.

“I volunteer for the trials in the hope that someone in the future, near or far, will benefit,” she says.

She feels that this is a part of her obligation as a Parkinson’s patient, to be an advocate and ambassador, and to carry on fighting the disease.

She adds: “I will not let this defeat me.”