Jul 21 2017

Scientists at UBC’s Okanagan campus have constructed a miniature device - using a 3D printer -that can screen quality of drinking water in real time and help protect against waterborne illness.

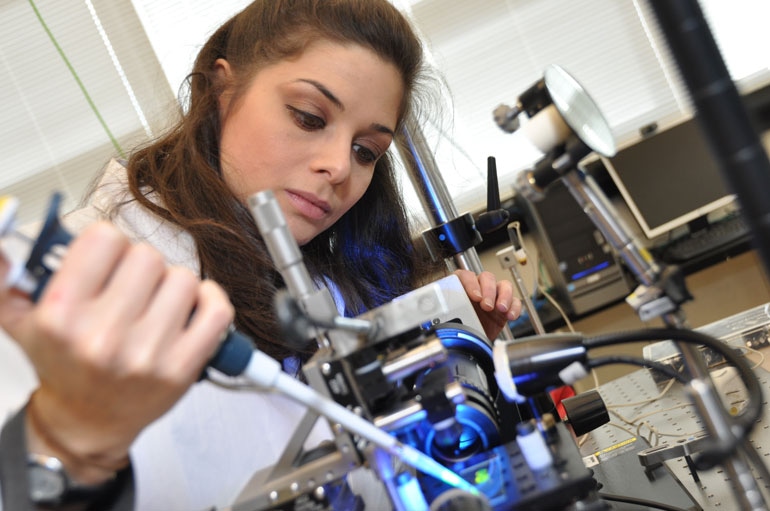

UBC Okanagan Professor Mina Hoorfar at work in her Advanced Thermo-Fluidic lab. (Credit: The University of British Columbia)

UBC Okanagan Professor Mina Hoorfar at work in her Advanced Thermo-Fluidic lab. (Credit: The University of British Columbia)

Prof. Mina Hoorfar, Director of the School of Engineering, says new research proves their miniaturized water quality sensors are economical to create, can function continuously and can be positioned anywhere in the water distribution system.

Current water safety practice involves only periodic hand testing, which limits sampling frequency and leads to a higher probability of disease outbreak. Traditional water quality sensors have been too expensive and unreliable to use across an entire water system.

Prof. Mina Hoorfar, Director of the School of Engineering

Until now, that is. Miniature devices built in her Advanced Thermo-Fluidic lab at UBC’s Okanagan campus, are proving dependable and sufficiently robust to provide accurate readings irrespective of water temperature or pressure. The sensors are wireless, reporting back to the testing stations, and work autonomously — meaning that if one stops functioning, it does not stall the entire system. And since they are created using 3D printers, they are quick, inexpensive and simple to produce.

This highly portable sensor system is capable of constantly measuring several water quality parameters such as turbidity, pH, conductivity, temperature, and residual chlorine, and sending the data to a central system wirelessly. It is a unique and effective technology that can revolutionize the water industry.

Prof. Mina Hoorfar, Director of the School of Engineering

Although a number of urban purification plants have instantaneous monitoring sensors, they are upstream of the distribution system. Frequently, Hoorfar notes, the pressure at which water is supplied to the customer is a lot higher than what most sensors can handle. But her new sensors can be positioned within or right at a customer’s home, providing a direct and accurate layer of protection against unsafe water.

And when things go erroneous, they can end disastrously. About 17 years ago, four people died and hundreds became ill, after consuming E.coli-affected water in Walkerton, Ontario.

Although the majority of water-related diseases occur in lower- or middle-income countries, water quality events in Walkerton, for example, raise serious questions about consistent water safety in even developed countries like Canada,” says Hoorfar. “Many of these tragedies could be prevented with frequent monitoring and early detection of pathogens causing the outbreak.

Prof. Mina Hoorfar, Director of the School of Engineering

Recently published in Sensors, this research was partially funded by the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada Strategic Project Grant and Postgraduate Scholarship funding.