Jun 25 2018

(Image Credit: Jamani Caillet/2018 EPFL)

(Image Credit: Jamani Caillet/2018 EPFL)

Scientists have developed a novel method of tracking the growth and spread of tumor cells; by drinking a solution that contains millions of tiny electronic sensors.

What would it be like if patients were able to track the progression of diseased cells in real time, just by drinking a glass of water that consists of millions of tiny electronic biosensors? Upon being ingested, the microscopic sensors would move to the diseased tissue in the body of a patient and send out an uninterrupted stream of diagnostic data through telemetry.

This is precisely the aspiring aim set by Sandro Carrara from EPFL’s Integrated Systems Laboratory (School of Engineering/Computer and Communication Sciences) and Pantelis Georgiou from Imperial College London for themselves.

At present, such technology looks achievable due to advancements in nanofabrication processes for integrated circuits. In 2013, scientists from the Berkeley Lab had discussed a similar concept in which suggestions were made to scatter CMOS circuits into the human cortex for monitoring neural activity.

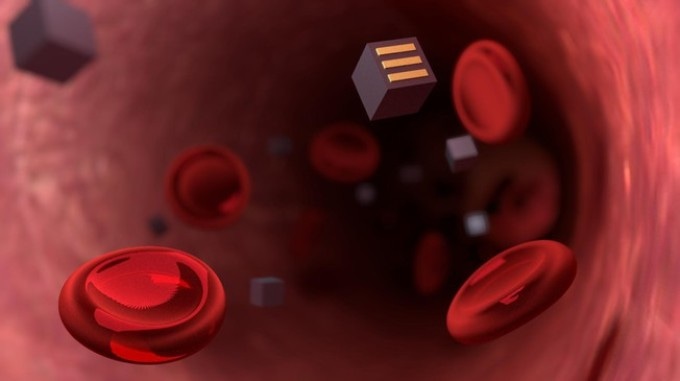

At EPFL, the scientists plan to use body dust for a more general purpose. They have already demonstrated ways for theoretically developing a CMOS cube with each side measuring 10 µm. They presented the study outcomes at the IEEE BioCAS conference. The theoretical possibility of the concept has also been discussed in a preprint on arXiv.

The researchers anticipate transformation of diagnostic methods and enabling doctors to gain better insights into diseases such as cancer.

Today doctors give drugs to cancer patients and wait to see whether the tumor cells go away. But having continuous feedback on how the cells respond to a given treatment would be of unprecedented value."

Sandro Carrara, Lead Scientist

The shape of the microscopic sensors would be cubic and they would be equipped with three complementary electrodes on their surfaces. Upon being swallowed by a patient, the sensors would pass through the intestinal walls through endocytosis, a natural process.

However, this process can take place only when the body of the patient considers the sensors to be red blood cells or bacteria. Therefore, the researchers intend to use a special coating to cover the sensors and shrink them to 10 µm on each side.

Immediately after entering the bloodstream, the sensors would move to the affected area and secure themselves to diseased cells with the help of targeted ligands such as antibodies. From there, they will be able to track the progress of the disease.

The sensors would function similar to spies, providing information related to, for instance, the metabolism of a cancer cell or the local concentration of an administered drug. A wireless energy transmission system would be used to gather the data.

The electrodes on the sensors’ surfaces would be able to identify the right protein or drug molecule they come into contact with, because each type of molecule would alter the current in a different way.

An electromagnetic field or ultrasound waves would be generated outside a patient’s body to charge the sensors and collect data. The sensors won’t contain batteries."

Sandro Carrara, Lead Scientist

To elaborate their concept, the researchers referred to concrete examples in the relevant works, such as glucose sensors of around 10 µm in which CMOS circuits are used, and a simple glucose sensor with a diameter of only 2.5 µm.

In 2016, a telemetric diagnostic device with 10 mm dimensions, covered with a biocompatible epoxy resin, was already tested successfully on mice. Yet, the research group has to overcome substantial obstacles.

First, they will have to reduce the size of the sensors to below 10 µm on each side, so that the size of the sensors is nearly the same size as red blood cells. Subsequently, they must show that possibility of applying their technology as well as the charging system.

Are there any side effects of these tiny sensors? At present, it is very early to say. The researchers are confident that the sensors can be easily removed from the body of a patient, either while removing the tumor itself or, if it is found that there are no diseased tissues, through the stool or urine of the patient.