Apr 2 2019

In the coming days, motorists will no longer continuously track traffic while driving. As a result, sensors integrated into autonomous vehicles need to be highly reliable.

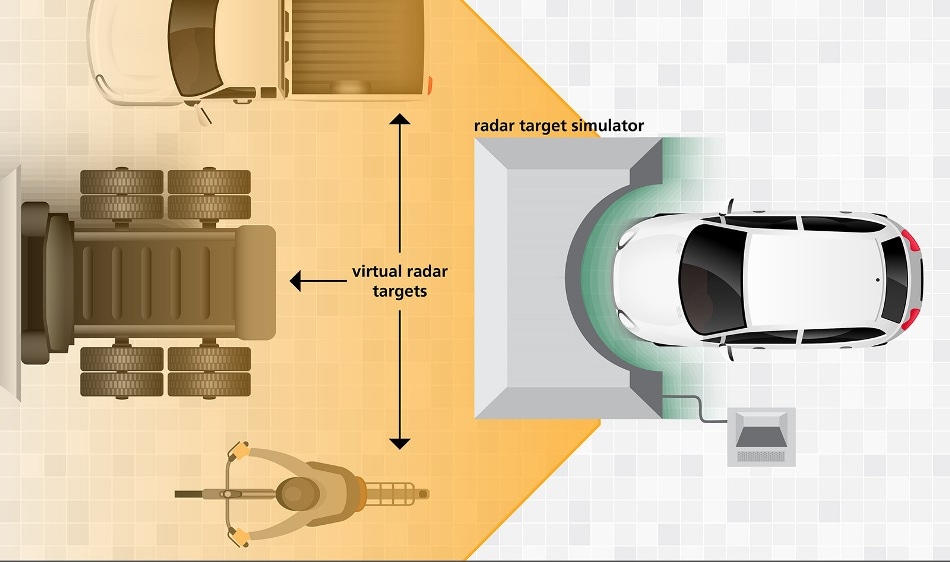

Illustration of the ATRIUM radar target simulator. (Image credit: Fraunhofer FHR)

Illustration of the ATRIUM radar target simulator. (Image credit: Fraunhofer FHR)

Fraunhofer Institute for High Frequency Physics and Radar Techniques FHR has developed a novel ATRIUM testing device using which a huge part of these road tests can be moved to the laboratory. The new device puts on a show for the radar sensor of the vehicle, creating artificial scenery that comes extremely close to the real scenarios faced in street traffic.

Future cars will be able to drive themselves. Passengers will travel down the road as if they are being chauffeured by a private driver while they read a newspaper, enjoy some conversation, or maybe watch a video. While driver assistance systems like automatic distance control are not new to the market, it will take some more years before fully autonomous vehicles can be driven in the streets. The reason for this is that the technology involved needs to be completely reliable. Here, the deciding factor is sensors—for instance, these days, radar sensors already have the potential to autonomously identify obstacles and apply the brakes in the event of danger. These radar sensors and other types of sensors are strictly tested prior to installing them in the car. In the case of autonomous vehicles, an even greater level of reliability is required because if the driver is not controlling the wheel, then it may ultimately become the responsibility of vehicle manufacturers to prevent an accident.

That is the reason why automobile producers have considerably high demands where the reliability of the sensor is concerned. They need sensors that do not induce more than one error over driving distances of many million kilometers. This implies that the present generation of cars usually needs to complete extremely long and tedious road tests.

That’s a lot of kilometers. On top of that, multiple sensors have to be tested in order to statistically prove their reliability. This means several test vehicles with sensors have to spend quite a long time on the road.

Dr.-Ing. Thomas Dallmann, Leader Research Group Aachen, Fraunhofer Institute for High Frequency Physics and Radar Techniques

There is another challenge—in case an error takes place following several thousand kilometers, then the sensor would need to be improved and the road tests have to be started all over again, a process that is highly time-intensive.

Moving road tests to the lab

In order to ease this scenario, efforts are being made to replicate reality and move the road tests to the lab settings. In this regard, such a type of lab test is already there for radar sensors, which release a radio signal that gets reflected by numerous objects. On the basis of echo, electronic sensor systems can subsequently examine the surroundings, and thus determine the distance to the identified objects and the speed at which they are traveling.

Using the so-called radar target simulators, this principle has already been replicated in a laboratory setting. Such a target simulator gathers the radar waves produced by the vehicle radar and then alters the radar signal to act as if it had actually met objects. This simulator subsequently sends the data to the car by way of an artificial echo image. The radar target simulator, therefore, creates a simulated landscape for the radar of the vehicle. The benefit is very clear—the test rig equipped with radar target simulator and a car radar can run in the lab round the clock, without the necessity to deploy a vehicle onto the street.

Regrettably, the few commercially available radar target simulators on the market today are incapable of creating a fully echo landscape.

Most of the models can only generate a highly restricted image with a single-digit number of reflections returned to the car’s radar. That’s an extremely small number compared to the situation in a natural environment.

Dr.-Ing. Thomas Dallmann, Leader Research Group Aachen, Fraunhofer Institute for High Frequency Physics and Radar Techniques

After all, actual scenery includes an infinite number of reflecting objects such as people, traffic signals, trees, and cars. Various reflections can be generated from different angles by even one vehicle in traffic, for instance, a passenger car whose side-view mirrors, wheels, and bumpers reflect in a different way.

“We’re still very far removed from a realistic setting when it comes to testing sensors for autonomous driving,” continued the engineer.

Radar target simulator generates as many as 300 reflections

That is why Dallmann and his group are in the process of creating a novel, better performance radar target simulator, referred to as ATRIUM (the German acronym for “Automotive test environment for radar in-the-loop testing and measurements”), that has the potential to create considerably more reflecting objects. Fraunhofer FHR’s present objective is to create 300 reflections by the end of the project, which is indeed a remarkable objective. “This will mean that ATRIUM can present the car’s radar sensor with a relatively true-to-life scene, something like a drive-in movie for the radar sensor,” added Dallmann.

Thomas Dallmann cannot describe the complete details yet because a patent application has been filed for the novel ATRIUM technology.

However, he stated that “We have optimized the structure of the transmission channels, making them much more cost-effective. As a result, the reflections can be represented in such a way that they reach the radar from a number of different directions.”

Such an approach can make it viable to test a new range of sensors for autonomous vehicles in complete scope and under extremely realistic conditions in the laboratory setting.

“In the future, we’ll be able to run highly complex tests, which will make it possible to greatly reduce the time involved in road tests.” Along with his colleagues, Dallmann will present the lab test facility with the ATRIUM radar target simulator and the vehicle radar at the Automotive Testing Expo in Stuttgart o be held from May 21st to 23rd, 2019.