Apr 26 2019

Next-generation fitness sensors could offer in-depth understanding of human health via noninvasive testing of bodily fluids. A stretchy patch created at KAUST could help this method by making it easier to examine sweat for important biomarkers.

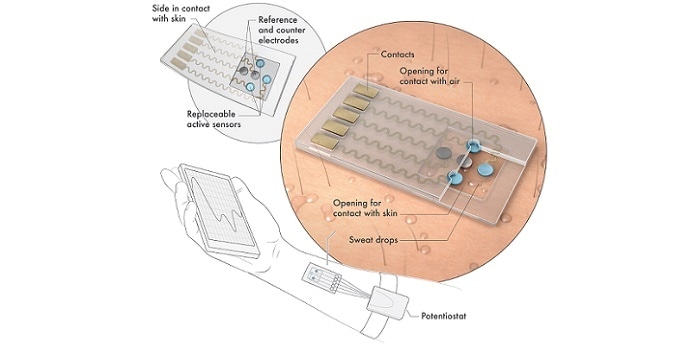

A schematic diagram of the sensor system showing how the drops of sweat are directed toward the electrodes that are coated with enzymes that can detect low concentrations of target compounds. (Reproduced with permission from reference 1 © 2019 John Wiley & Sons)

A schematic diagram of the sensor system showing how the drops of sweat are directed toward the electrodes that are coated with enzymes that can detect low concentrations of target compounds. (Reproduced with permission from reference 1 © 2019 John Wiley & Sons)

Human perspiration has trace quantities of organic molecules that can serve as measurable health signs—glucose variations, for instance, may indicate to blood sugar disorders, while high levels of lactic acid could point to oxygen deficiencies. To spot these molecules, scientists are creating flexible prototypes that can be placed on the skin and direct sweat toward special enzyme-coated electrodes. The specific nature of enzyme-substrate binding allows these sensors to electrically notice extremely low concentrations of target compounds.

One hurdle with enzyme biosensors, however, is their comparatively short lifetimes.

Even though human skin is quite soft, it can delaminate the enzyme layer right off the biosensor.

Yongjiu Lei, Ph.D. student, KAUST.

Lei and his colleagues in Husam Alshareef’s team have currently designed a wearable system that can endure the harshness of skin contact and deliver enhanced biomarker detection. Their device works on a thin, flat ceramic called MXene that looks like graphene but has a blend of titanium and carbon atoms. The metallic conductivity and low toxicity of this 2D material make it a suitable platform for enzyme sensors, according to new studies.

The researchers attached minute dye nanoparticles to MXene flakes to increase its sensitivity to hydrogen peroxide, the key by-product of enzyme-catalyzed reactions in sweat. Then, they compressed the flakes in mechanically tough carbon nanotube fibers and conveyed the composite onto a membrane engineered to draw sweat through without pooling. A last coating of glucose or lactose-oxidase enzymes concluded the electrode assembly.

The new electrodes could be frequently swapped in or out of a stretchy polymer patch that both captures sweat and conveys the measured signals of hydrogen peroxide to an outer source, such as a smartphone. When the researchers added the biosensor into a wristband worn by volunteers riding immobile bicycles, they saw lactose concentrations in sweat increase and drop in keeping with workout intensities. Variations in glucose levels could also be monitored as accurately in sweat as it is in blood.

“We are working with KAUST and international collaborators under the umbrella of the Sensors Initiative to integrate tiny electrical generators into the patch,” says Alshareef, who led the project. “This will enable the patch to create its own power for personalized health monitoring.”

Nanotech-powered electrodes help solve the challenges of using sweat to assess biological conditions in real time. (© KAUST 2019)