Nov 20 2019

Researchers from Trinity College Dublin have developed a set of new biological sensors by chemically re-engineering pigments to behave like miniature Venus flytraps. The sensors have the ability to identify and grab particular molecules, such as pollutants, and will soon have a multitude of critical environmental, security, and medical applications.

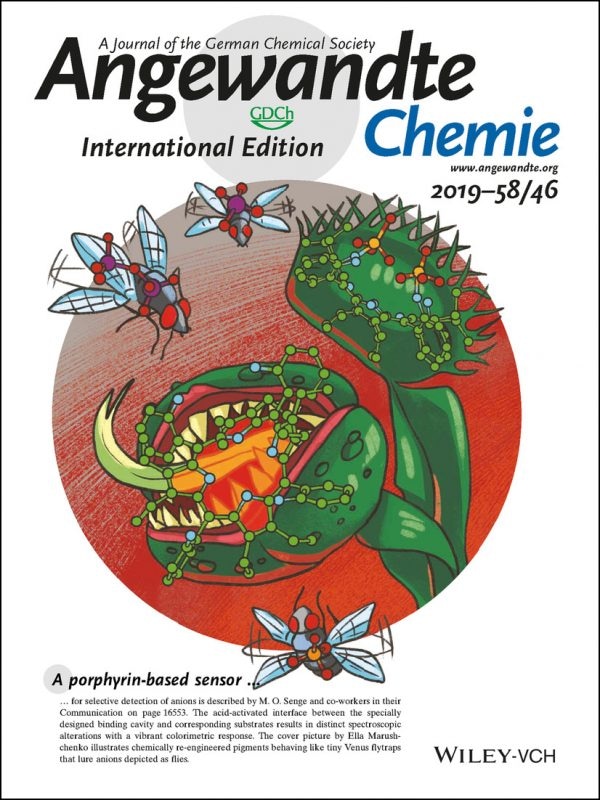

The research is featured as a hot paper and has also been selected as the journal’s cover illustration. Image Credit: Trinity College Dublin.

The research is featured as a hot paper and has also been selected as the journal’s cover illustration. Image Credit: Trinity College Dublin.

Porphyrins, an exclusive category of intensely colored pigments—also called the “pigments of life”—offer the key to this revolutionary innovation. The word porphyrin is based on the Greek word “porphura,” meaning purple, and the first chapter describing the medical-chemical history of porphyrins dates back to the times of Herodotus (circa 484 to 425 BC).

This theory has been developing ever since and is at the core of Professor Mathias O. Senge’s research efforts at Trinity.

In living organisms, porphyrins have a vital role to play in metabolism, with the most obvious examples being heme (the red blood cell pigment that conveys oxygen) and chlorophyll (the green plant pigment that harvests light and triggers photosynthesis).

By nature, the active versions of these molecules contain different metals in their core, which results in a set of distinctive properties.

The scientists at Trinity, under the direction of Professor Mathias O. Senge, Chair of Organic Chemistry, selected a disruptive method of investigating the metal-free version of porphyrins. Their study has developed a completely new range of molecular receptors.

By pushing porphyrin molecules to turn inside out, into the shape of a saddle, they could manipulate the previously inaccessible core of the system. Then, by adding functional groups near the active center, they were able to capture small molecules—such as agricultural or pharmaceutical pollutants, for example, sulfates and pyrophosphates—and then keep them in the receptor-like cavity.

Porphyrins are color-intense compounds; therefore, if a target molecule is trapped, this causes a drastic change in the color. This emphasizes the value of porphyrins as biosensors as it is evident when they have effectively trapped their targets.

These sensors are like Venus flytraps. If you bend the molecules out of shape, they resemble the opening leaves of a Venus flytrap and, if you look inside, there are short stiff hairs that act as triggers. When anything interacts with these hairs, the two lobes of the leaves snap shut.

Karolis Norvaiša, Study First Author and PhD Researcher, Trinity College Dublin

Karolis Norvaiša continued, “The peripheral groups of the porphyrin then selectively hold suitable target molecules in place within its core, creating a functional and selective binding pocket, in exactly the same way as the finger-like projections of Venus flytraps keep unfortunate target insects inside.”

Karolis Norvaiša is supported by the Irish Research Council. The discovery was recently reported in the print version of the leading international journal Angewandte Chemie International Edition.

The research underlines the start of an EU-wide H2020 FET-OPEN project known as INITIO, the objective of which is to identify and eliminate pollutants. The study was possible because of the preliminary funding from Science Foundation Ireland and an August-Wilhelm Scheer guest professorship award for Professor Senge at the Technical University of Munich.

Gaining an understanding of the porphyrin core’s interactions is an important milestone for artificial porphyrin-based enzyme-like catalysts. We will slowly but surely get to the point where we can realise and utilise the full potential of porphyrin-substrate interfaces to remove pollutants, monitor the state of the environment, process security threats, and deliver medical diagnostics.

Mathias O. Senge, Professor and Chair of Organic Chemistry, Trinity College Dublin