Researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics performed a comparative research on the simultaneous processing of the brain of stimuli from various senses by non-musicians and musicians.

They utilized functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and mapped the active brain regions during the process. The researchers found that pianists develop a special sense of temporal correlation between the sound of the notes being played and the piano key movements. But, pianists were not better than non-musicians at estimating the synchronicity between speech and lip movements, they noted.

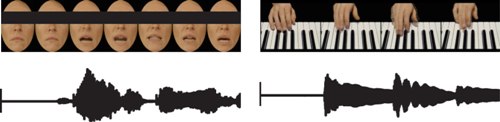

A segment of the audiovisual speech (left) and music (right) stimulus. Credit: HweeLing Lee/MPI for Biological Cybernetics

A segment of the audiovisual speech (left) and music (right) stimulus. Credit: HweeLing Lee/MPI for Biological Cybernetics

The perception of asynchronous hand movements and music initiates more error signals in a circuit, which involves the premotor, the cerebellum and related brain regions. The study revealed that a person’s sensorimotor experience influenced the brain’s way of temporally linking the different signals from the various senses.

Uta Noppeney and HweeLing Lee at the Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics showed the integration of stimuli from the various senses and the changes in brain circuitry due to learning. They compared amateur pianists and non-musicians over finger movements, piano music, lip movements and spoken sentences. In the study, the mouth or finger movements were delayed or advanced according to sounds heard at 360 ms. The participants were asked to specify synchronous or asynchronous events. Later, they were made to undergo the same experiment under fMRI, when they were asked to remain passive, while the machine recorded the brain areas that became active.

The study showed that pianists were more precise at judging coincidence of sounds heard and finger movements. Uta Noppeney explained that due to piano practice, a forward model involved the premotor cerebral cortex and the cerebellum was programmed in the circuit, which allowed the person to make better predictions about the exact temporal sequence. The study indicated how the brain can react to sensorimotor experience in a flexible manner.