Oct 24 2013

A remote acoustic detection system designed to identify homemade bombs can determine the difference between those that contain low-yield and high-yield explosives.

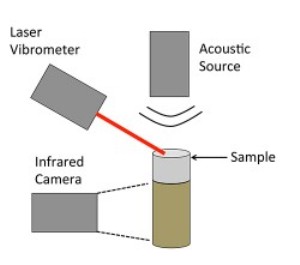

Schematic of the experiment setup. (Douglas Adams / Vanderbilt)

Schematic of the experiment setup. (Douglas Adams / Vanderbilt)

That capability – never before reported in a remote bomb detection system – was described in a paper by Vanderbilt engineer Douglas Adams presented at the American Society of Mechanical Engineers Dynamic Systems and Control Conferenceon Oct. 23 in Stanford, CA.

A number of different tools are currently used for explosives detection. These range from dogs and honeybees to mass spectrometry, gas chromatography and specially designed X-ray machines.

“Existing methods require you to get quite close to the suspicious object,” said Adams, Distinguished Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering. “The idea behind our project is to develop a system that will work from a distance to provide an additional degree of safety.”

Using sound waves for bomb detection

Adams is developing the acoustic detection system with Christopher Watson and Jeffrey Rhoads at Purdue University and John Scales at the Colorado School of Mines as part of a major Office of Naval Research grant.

The new system consists of a phased acoustic array that focuses an intense sonic beam at a suspected improvised explosive device. At the same time, an instrument called a laser vibrometer is aimed at the object’s casing and records how the casing is vibrating in response. The nature of the vibrations can reveal a great deal about what is inside the container.

“We are applying techniques of laser vibrometry that have been developed for non-destructive inspection of materials and structures to the problem of bomb detection and they are working quite well,” Adams said.

In the current experiments, the engineers created two targets. One used an inert material that simulates the physical properties of low-yield explosive. The other was made from a simulant of high-yield explosive. They were fastened to acrylic caps to simulate plastic containers. Mechanical actuators substituted for the acoustic array to supply the sonic vibrations. The laser vibrometer was focused on the top of the plastic cap, corresponding to the outside of the bomb casing.

The tests clearly showed differences in the vibration patterns of the two caps that allow the researchers to distinguish between the two materials (hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene polymer embedded with 50 percent and 75 percent by volume ammonium chloride crystals).

At the conference, Adams also showed a video of another test of the acoustic technique that showed it can differentiate between an empty container, one filled with water and one filled with a clay-like substance. The test used one-gallon plastic milk containers. In this case, the acoustic waves were produced by a device called an air driver. The empty jug had the largest vibrations while the jug containing the clay-like material had the smallest vibrations. The vibrations of the water-filled jug were in between.

The researchers have established that the best way to detect the contents of devices made of rigid material like metal is to use short ultrasonic waves. On the other hand, longer subsonic and infrasonic waves can be used to penetrate softer materials like plastics. Adam’s colleagues at Purdue are studying frequencies that can penetrate other materials like cloth.

The project is part of a $7 million multi-university research initiative led by North Carolina State University and funded by Office of Naval Research grant N00014-10-1-0958.