Apr 30 2014

“Up periscope!” may become a submarine commander's outdated order, thanks to a team of Technion-Israel Institute of Technology researchers who have developed a new technology for viewing objects above the water's surface without a periscope poking its head above the waves.

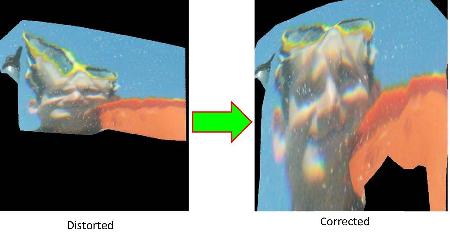

Distorted (left) and corrected views from underwater

Distorted (left) and corrected views from underwater

The technology behind a submerged, “virtual periscope” will be introduced in a presentation at the IEEE International Conference on Computational Photography, held May 2-4, 2014 in Santa Clara, Calif.

Associate Professor Yoav Y. Schechner, of the Technion Department of Electrical Engineering, and colleagues, developed the virtual periscope called “Stella Maris” (Stellar Marine Refractive Imaging Sensor). The heart of the underwater imaging system is a camera, a pinhole array to admit light (a thin metal sheet with precise, laser-cut holes), a glass diffuser, and mirrors. Sunrays are projected through the pinholes to the diffuser, which is imaged by the camera, beside the distorted object of interest. The latter is then corrected for distortion.

“Raw images taken by a submerged camera are degraded by water-surface waves similarly to degradation of astronomical images by our atmosphere. We borrowed the concept from astronomers who use the Shack-Hartmann astronomical sensor on telescopes to counter blurring and distortion caused by layers of atmosphere,” explains Schechner. “Stella Maris is a novel approach to a virtual periscope as it passively measures water and waves by imaging the refracted sun.”

The unique technology gets around the inevitable distortion caused by the water-surface waves when using a submerged camera, according to Schechner, because of the sharp refractive differences between water and air, random waves at the interface present distortions that are worse than the distortion atmospheric turbulence creates for astronomers peering into space.

“When the water surface is wavy, sun-rays refract according to the waves and project onto the solar image plane,” explains Schechner. “With the pinhole array, we obtain an array of tiny solar images on the diffuser.” When all of the components work together, the Stella Maris system acts as both a wave sensor to estimate the water surface, and a viewing system to see the above surface image of interest through a computerized, “reconstructed” surface.

The Stella Maris virtual periscope is just the latest technology developed by the researchers, who have also found ways to exploit “underwater flicker,” i.e., random change of underwater lighting, caused by the water surface wave motion. Members in the Schechner Hybrid Imaging Lab turned the tables on underwater flicker and used the natural rapid and random motion of the light beams to obtain three-dimensional mapping of the sea floor.

According to the developers, the virtual periscope may have potential uses in addition to submarines, where they could reduce the use of traditional periscopes that have been in use for more than a century. Submerged on the sea floor, Stella Maris could be useful for marine biology research where and when viewing and imaging both beneath and above the waves simultaneously is important. Stella Maris could, for example, monitor the habits of seabirds as they fly, then plunge into water and capture prey.

“There are many ways to advance the virtual periscope,” says Schechner, who adds that while the system requires sunlight, they are currently working on a way to gather enough light from moonlight or starlight to be able to use the system at night.