Jun 16 2014

Referees may soon have a new way of determining whether a football team has scored a touchdown or gotten a first down.

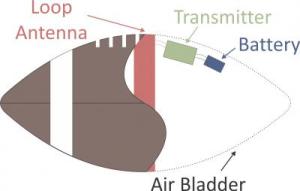

Researchers have developed a system that can track a football in three-dimensional space using low-frequency magnetic fields. Credit: David Ricketts

Researchers have developed a system that can track a football in three-dimensional space using low-frequency magnetic fields. Credit: David Ricketts

Researchers from North Carolina State University and Carnegie Mellon University, in collaboration with Disney Research, have developed a system that can track a football in three-dimensional space using low-frequency magnetic fields.

The technology could be particularly useful for situations when the ball is blocked from view, such as goal-line rushing attempts when the ball carrier is often buried at the bottom of a pile of players. The technology could also be useful for tracking the forward progress of the ball, or for helping viewers follow the ball during games with low visibility – such as games played during heavy snow.

Previous attempts to design technology that tracks the position of a football have used high frequency radio waves. But these high frequency waves are absorbed by players and can be thwarted by the complex physical environment of a football stadium. Because the technology would be most useful in pile-ups, when the ball is obscured by players, these high-frequency approaches aren't practical – the absorbed radio waves would result in incorrect or incomplete data on where the ball is located.

"But low frequency magnetic fields don't interact very strongly with the human body, so they are not affected by the players on the field or the stadium environment," says Dr. David Ricketts, an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering at NC State and senior author of a paper describing the research. "This is part of what makes our new approach effective.

The researchers designed and built a low frequency transmitter that is integrated into a football, and is within the standard deviation of accepted professional football weights. In other words, the football that has the built-in transmitter could be used in a National Football League game. Antennas, placed around the football field, receive signals from the transmitter and track its location.

But the researchers also had to address another complicating factor.

When low frequency magnetic fields come into contact with the earth – such as the playing surface – the ground essentially absorbs the magnetic field and re-emits it. This secondary field interacts with the original field and confuses the antennas, which can throw off the tracking system's accuracy.

"We realized that we could use a technique developed in the 1960s called complex image theory," says Dr. Darmindra Arumugam, lead author of the paper and a former Ph.D. student at Carnegie Mellon now at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. "Complex image theory allows us to account for the secondary fields generated by the earth and compensate for them in our model."

"We're still fine-tuning the system, but our goal is to get the precision down to half the length of a football, which is the estimated margin of error for establishing the placement of the football using eyesight alone," Ricketts says.