May 19 2017

A small, thin square of an organic plastic that can detect disease markers in breath or toxins in a building's air could soon be the basis of portable, disposable sensor devices. By perforating the thin plastic films with pores, University of Illinois Researchers made the devices sufficiently sensitive to detect at levels that are far too low to smell, yet are vital to human health.

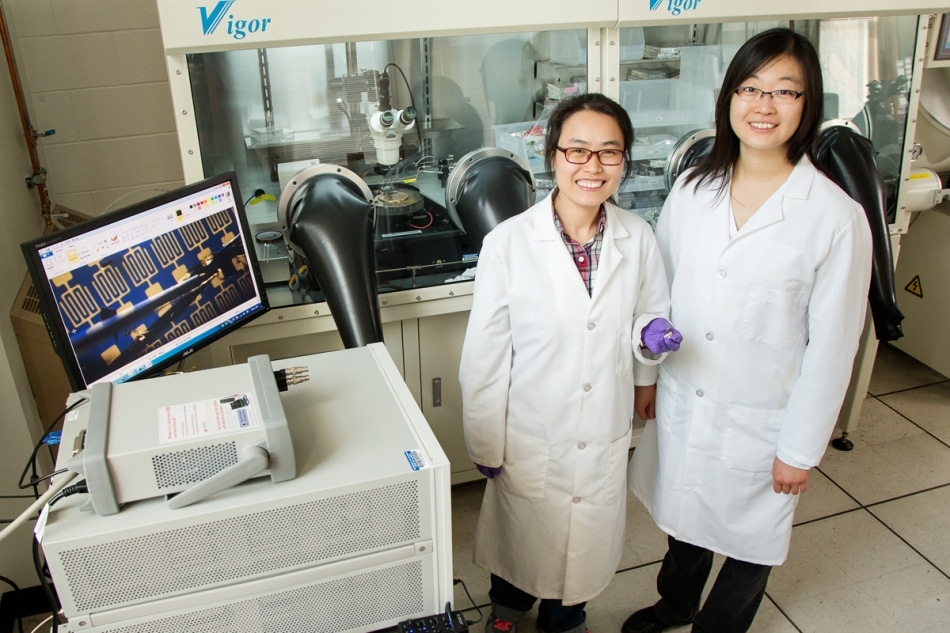

Postdoctoral researcher Fengjiao Zhang and Professor Ying Diao developed devices for sensing disease markers in breath. (Photo by L. Brian Stauffer)

Postdoctoral researcher Fengjiao Zhang and Professor Ying Diao developed devices for sensing disease markers in breath. (Photo by L. Brian Stauffer)

In a recent research published in the journal Advanced Functional Materials, Professor Ying Diao’s research team exhibited a device that screens ammonia in breath, an indication of kidney failure.

In the clinical setting, physicians use bulky instruments, basically the size of a big table, to detect and analyze these compounds. We want to hand out a cheap sensor chip to patients so they can use it and throw it away.

Professor Ying Diao, Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, University of Illinois

Other Researchers have attempted using organic semiconductors for gas sensing, but the materials were not sufficiently sensitive to detect trace levels of disease markers in breath. Diao’s team understood that the reactive sites were not on the surface of the plastic film, but within it.

We developed this method to directly print tiny pores into the device itself so we can expose these highly reactive sites. By doing so, we increased the reactivity by ten times and can sense down to one part per billion.

Professor Ying Diao, Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, University of Illinois

In their first device demonstration, the team concentrated on ammonia as a marker for kidney failure. Monitoring the variation in ammonia concentration could provide a patient an early warning sign to check with their Doctor and go for a kidney function test, Diao said.

The material they selected is extremely reactive to ammonia but not to other compounds in breath, Diao said. But by modifying the composition of the sensor, they could engineer devices that are tuned to other compounds. For instance, the Researchers have built an ultra-sensitive environmental monitor for formaldehyde, a typical indoor pollutant in refurbished or new buildings.

The team is working to build sensors with numerous functions to get a more wholesome picture of a patient’s health.

We would like to be able to detect multiple compounds at once, like a chemical fingerprint. It’s useful because in disease conditions, multiple markers will usually change concentration at once. By mapping out the chemical fingerprints and how they change, we can more accurately point to signs of potential health issues.

Professor Ying Diao, Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, University of Illinois

Diao’s team worked together with Purdue University professor Jianguo Mei on this research.