May 23 2018

To date, trained rescue dogs have been incomparable disaster workers as their strong sense of smell helps them locate people buried by avalanches or earthquakes. However, similar to all other living beings, even dogs have to take breaks once in a while.

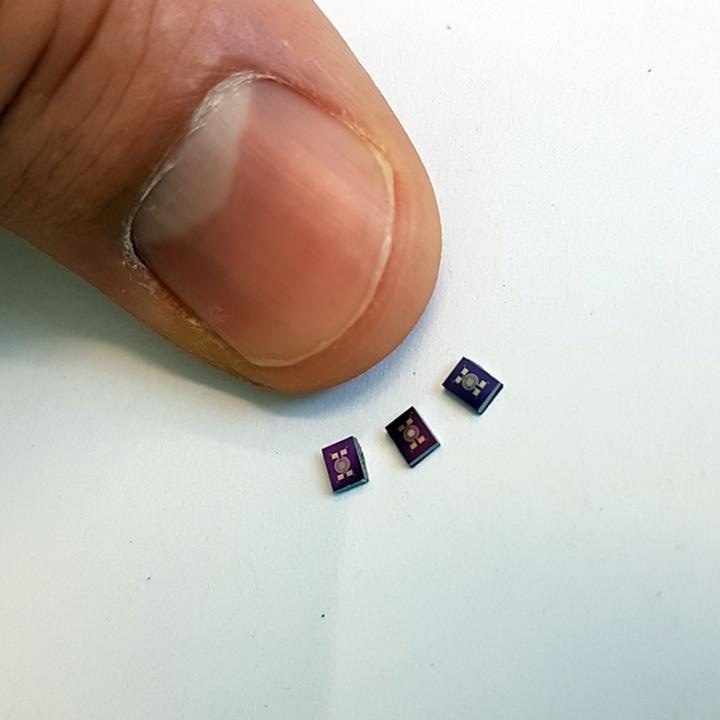

The three gas sensors developed at ETH Zurich. (Image credit: ETH Zurich/Andreas Güntner)

The three gas sensors developed at ETH Zurich. (Image credit: ETH Zurich/Andreas Güntner)

Moreover, they are usually not available immediately in disaster areas, and dog teams have to travel from places afar.

Scientists from ETH Zurich, headed by Professor of Process Engineering Sotiris Pratsinis, have developed an innovative measuring device that can be readily used at any time. Earlier they had created tiny, highly sensitive gas sensors for sensing isoprene, ammonia, and acetone, which are all metabolic products liberated in lower concentrations through our skin or breath. At present, they have incorporated these sensors into a device with two commercial sensors for sensing moisture and CO2.

Chemical “Fingerprint”

Through laboratory tests, Austrian and Cypriot researchers have demonstrated that this sensor combination can be absolutely helpful while looking for entrapped people. A test chamber at the University of Innsbruck’s Institute for Breath Research in Dornbirn was used as an entrapment simulator. Each volunteer stayed in this chamber for two hours.

“The combination of sensors for various chemical compounds is important because the individual substances could come from sources other than humans. CO2, for example, could come from either a buried person or a fire source,” explained Andreas Güntner, lead author of the study, who is a postdoc in Pratsinis’ group. The study has been reported in the Analytical Chemistry journal. The sensor combination offers reliable indicators of the presence of people.

Suitable for Inaccessible Areas

Moreover, the scientists demonstrated the differences between the compounds liberated through our skin and breath.

“Acetone and isoprene are typical substances that we mostly breathe out. Ammonia, however, is usually emitted through the skin,” elucidated ETH professor Pratsinis.

As part of the experiments using the entrapment simulator, a breathing mask was worn by the participants. In the first step, the exhaled air was directly channeled out of the chamber; in the second step, it was restricted inside. This enabled the researchers to develop separate emission profiles for skin and breath.

The size of the gas sensors developed by the ETH researchers was equal to that of a small computer chip.

They are about as sensitive as most ion mobility spectrometers, which cost thousands of Swiss francs and are the size of a suitcase. Our easy-to-handle sensor combination is by far the smallest and cheapest device that is sufficiently sensitive to detect entrapped people. In a next step, we would like to test it during real conditions, to see whether it is suited for use in searches after earthquakes or avalanches.

Sotiris Pratsini, Professor of Process Engineering

Although electronic devices are already in use for searches following earthquakes, they operate with cameras and microphones. They can be used only to locate entrapped people who can make themselves heard or are visible from under the ruins. The concept of the ETH researchers is to complement these devices with the chemical sensors. At present, they are looking for investors or industry partners to support the development of a prototype. It could also be possible to equip robots and drones with the gas sensors, enabling inaccessible or difficult-to-reach areas to be searched. They can be further used for exposing human trafficking and for detecting stowaways.