Jun 28 2014

By fusing together the concepts of active fiber sensors and high-temperature fiber sensors, a team of researchers at the University of Pittsburgh has created an all-optical high-temperature sensor for gas flow measurements that operates at record-setting temperatures above 800 degrees Celsius.

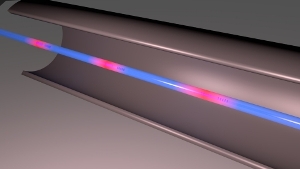

An artist's rendering of the fiber optic flow sensor. The glowing red sections along the optical fiber are the sensors--hundreds of these sensors can be packed into a single fiber. Image credit: Kevin Chen, University of Pittsburgh.

An artist's rendering of the fiber optic flow sensor. The glowing red sections along the optical fiber are the sensors--hundreds of these sensors can be packed into a single fiber. Image credit: Kevin Chen, University of Pittsburgh.

This technology is expected to find industrial sensing applications in harsh environments ranging from deep geothermal drill cores to the interiors of nuclear reactors to the cold vacuum of space missions, and it may eventually be extended to many others.

The team describes their all-optical approach in a paper published today in The Optical Society’s (OSA) journal Optics Letters. They successfully demonstrated simultaneous flow/temperature sensors at 850 C, which is a 200 C improvement on an earlier notable demonstration of MEMS-based sensors by researchers at Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

The basic concept of the new approach involves integrating optical heating elements, optical sensors, an energy delivery cable and a signal cable within a single optical fiber. Optical power delivered by the fiber is used to supply energy to the heating element, while the optical sensor within the same fiber measures the heat transfer from the heating element and transmits it back.

“We call it a 'smart optical fiber sensor powered by in-fiber light',” said Kevin P. Chen, an associate professor and the Paul E. Lego Faculty Fellow in the University of Pittsburg’s Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering.

The team’s work expands the use of fiber-optic sensors well beyond traditional applications of temperature and strain measurements. “Tapping into the energy carried by the optical fiber enables fiber sensors capable of performing much more sophisticated and multifunctional types of measurements that previously were only achievable using electronic sensors,” Chen said.

In microgravity situations, for example, it’s difficult to measure the level of liquid hydrogen fuel in tanks because it doesn’t settle at the bottom of the tank. It’s a challenge that requires the use of many electronic sensors—a problem Chen initially noticed years ago while visiting NASA, which was the original inspiration to develop a more streamlined and efficient approach.

“For this type of microgravity situation, each sensor requires wires, a.k.a. ‘leads,’ to deliver a sensing signal, along with a shared ground wire,” explained Chen. “So it means that many leads—often more than 40—are necessary to get measurements from the numerous sensors. I couldn’t help thinking there must be a better way to do it.”

It turned out, there is. The team looked to optical-fiber sensors, which are one of the best sensor technologies for use in harsh environments thanks to their extraordinary multiplexing capabilities and immunity to electromagnetic interference. And they were able to pack many of these sensors into a single fiber to reduce or eliminate the wiring problems associated with having numerous leads involved.

“Another big challenge we addressed was how to achieve active measurements in fiber,” Chen said. “If you study optical fiber, it’s a cable for signal transmission but one that can also be used for energy delivery—the same optical fiber can deliver both signal and optical power for active measurements. It drastically improves the sensitivity, functionality, and agility of fiber sensors without compromising the intrinsic advantages of fiber-optic sensors. That’s the essence of our work.”

Based on the same technology, highly sensitive chemical sensors can also be developed for cryogenic environments. “The optical energy in-fiber can be tapped to locally heated in-fiber chemical sensors to enhance its sensitivity,” Chen said. “In-fiber optical power can also be converted into ultrasonic energy, microwave or other interesting applications because tens or hundreds of smart sensors can be multiplexed within a single fiber. It just requires placing one fiber in the gas flow stream—even in locations with strong magnetic interference.”

Next, the team plans to explore common engineering devices that are often taken for granted and search for ways to enhance them. “For fiber sensors, we typically view the fiber as a signal-carrying cable. But if you look at it from a fiber sensor perspective, does it really need to be round or a specific size? Is it possible that another size or shape might better suit particular applications? As a superior optical cable, is it also possible to carry other types of energy along the fibers for long-distance and remote sensing?” Chen noted. “These are questions we’ll address.”